Create an Account

Create an account for powerful AI tools, award-winning courses, and access to our vibrant community.

or

Already have an account?

From a simple walk to a thrilling experience into an ancient world

A day like any other, but this time a native person guides us from Australia.

His name is Trent, and he is taking us for a quick tour around Adelaide Botanical Gardens.

With his plant knowledge, he is willing to show us the importance of species that changed the different Aboriginal group’s lifestyle over thousands of years. Plants that were once used to aid their survival in the bush, including many still used today. Some are only found in specific locations, within niche environments, known to Aboriginal peoples renowned nomads.

Different groups walk long distances (walkabout) around the country looking for food and shelter. During this process, they are not only consumers of nature but also conservationists. What has been taken out of place needs to be put back by planting, fixing bark wounds, aerating the soil, fishing in moderation and hunting wisely. The indigenous people of Australia understand these processes well.

These practices are specified by Trent along his walk through the gardens, pointing out different ancient techniques that are still used today, showing how efficient and safe bush life can be for local people with local knowledge.

To be more accurate, Trent comes from Kaurna (gar-na) people, located mainly in the Adelaide region, among 391 other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander language groups found within Australia.

Please, bear in mind that this knowledge has evolved for thousands of years, mainly through storytelling. And those able to tell ordinary people like me are golden relics, such as Trent. These storytellers probably spent their childhood around their elders, walking through the bush and reading nature as it unfolds before their eyes.

Nothing was written down. It is one of the reasons why Australian Aboriginal knowledge is under threat. They rely on telling stories along generations to create some sense of identity amongst themselves. But most of the stories were ignored, or even deceived by the first settlers during the colonisation period, according to Bruce Pascoe in his book “Dark Emu”.

Bruce is an Aboriginal Australian writer and historian who is trying to give more light to Aboriginal knowledge. Through his book, Mr Pascoe puts several essential points into perspective, especially the argument that “history has whitewashed” Aboriginal knowledge. His main idea is that Australia’s indigenous people have sophisticated agriculture techniques, but it has been denied over the years.

Apart from all the injustices towards the land peoples, some of us are still trying to understand plants’ wisdom, which Aboriginal people have accumulated over thousands of years. It is what this article will touch upon in the following few paragraphs.

Before we start, a question comes to mind. I shall let you answer quietly: Why do we continue to waste this critical recognition and appreciation towards an ancient history still ignored?

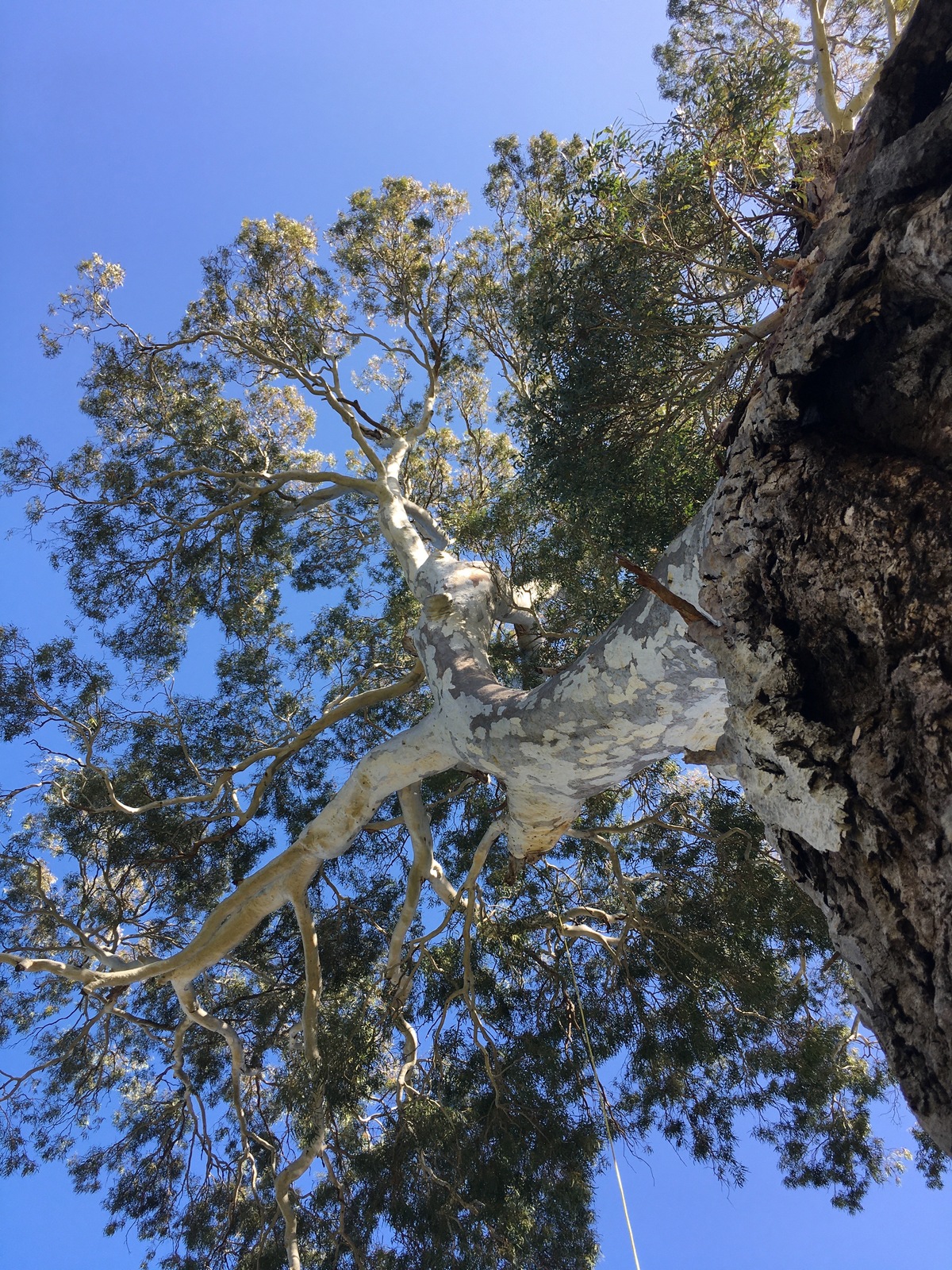

The Ancient River Redgum

Our first step is at the supermarket tree. A large, stunning old River redgum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) standing by itself amid other smaller plants. A massive wood hollow at the base indicates several battles fought along with its life long before Europeans came to South Australia.

According to Trent, his ancestors would walk past this tree carrying hunger within themselves. Possum and bird’s eggs are the typical inhabitants of hollows like this, often available throughout the canopy.

The skin of furry animals like brushtail and ringtail possums can give excellent insulation from severe weather to their naked bodies during walkabouts in the bush. If for an occasional stopover, possum meat can be a luxury that could feed the entire group. Instead of throwing away the bones, they were used as weapons and basic utensils, such as building tools, cutlery and crushers. As you can see, nothing goes to waste.

River redgums are notorious for their versatility amongst native peoples.

Commonly seen at museums, the bark is used to build canoes — perfect floating rafts that could help them cross territories and fishing with no worries.

It would take a handful of people to strip the bark off, bend it in specific ways and fix any holes with gum resin. They knew from the start that plants could provide whatever they need to get the job done. The beauty about it is that nothing is taken for granted.

The indigenous people’s sense of belonging to the land emancipates a level of respect that no white man today can understand. It is almost a blindfolded conservation practice guided by the wind, colours, temperature and smell, and they know exactly where they are going to end — Incredible.

To a Dinosaur-like plant

Trent introduced us to the grass tree, Yakka (Xanthorrhoea quadrangulata), not far from the supermarket tree. A unique tree that looks like tall grass, which it is, and is not much bigger than the lowest shrub in your backyard. Thus, with incredible superpowers, it is easy to shun it in the bush.

The kind of grass tree that would survive the most severe fire, thriving on it and willing to spread its seeds. It looks like a plant from the dinosaur era. A bit prickly at the tip of the long needle-like leaf, thus the locals would use the flower stalk to build tools once it dries out. This stick can also be handled as a spear to hunt small mammals.

Also, it is well-known for making fire. Continuous friction with a circular movement made by hand on top of a thin piece of paperbark is pure physics. Besides, the way grass trees grow (upright) can create small sheltering spots underneath the dry leaves.

Yakka (Xanthorrhoea quadrangulata) / Source: T. Miranda 2020

These are commonplace for small mammals escaping the weather, another food source at easy reach. When grass trees finish flowering, seeds are found in abundance to create flour or can even be roasted on the fire, making a handy pocket food.

Our walk was taken to a different complex world, neglected and misunderstood by most white people that grew up not hearing these stories. Stories that, nonetheless, are a show of nature unfolding before one’s eyes. The good thing is that Aboriginal people still know how to appreciate it.

Covered by Dominant Trees

A few more steps into the Australian forest represented by a section of the Botanical Gardens, you could see yourself embraced by many surprises. This time, Trent took us to a tree that resembles the giant baobabs (Adansonia spp.) in Africa. Yet being a completely different species, its swelling trunk and short limbs are not too far-flung to be the same.

These are bottle trees (Brachychiton rupestre). This one, specifically, is probably 15 metres tall and 2 metres wide at breast height (DBH), not a typical size for this tree in the bush. However, passing nomads would crack the bark open for water. Sometimes when the bark peels, they would have squeezed it for water, depending on the climate.

Once they were satisfied, there is the crucial job of sealing the broken piece back into the trunk, using mud to fix the wound, just like a plastering job done by nature. Until today, we do not know why they do it this way, but according to Trent, fixing the wound is an act of solidarity. They can foresee when they will come back to that same spot years later.

Even better, they were taught to leave things the way they are found in nature, undamaged, for others to use in the same way you did. I tend to call this attitude the apex of respect towards the community and nature.

Their understanding of giving back to nature makes them part of a cycle that probably would not be called a science. You may recall a fulfilled knowledge of the land, which science could easily explain, though distant from everyday awareness.

The Large Dead Trunk

As the day passed quickly, we could not miss the last standpoint — a colossal trunk hollow, far from being alive, still standing and vigorously intense. It is a perfect spot for sheltering and gathering when they plan for their continuous walk throughout the land.

Under tree hollows like this one are used as a reference point that almost every Aboriginal group would recognise. Somewhere you could light a fire, set up a camp, sleep tight and stay protected from the weather. You could not have asked for any better place to be after a long day of walking through the bush.

Large river redgum trunk / Source: T. Miranda 2020

This is where the native peoples were well ahead of us in accepting biodiversity and natural interrelationships as their allies. Their understanding of recycling, conservation, food, planting, nature reading, and respect is not around us, white people. At least, not at the Aboriginal Australian level.

We could learn a lot from their technologies that, one way or another, helped them survive for more than 60 000 years. Much longer than any other empire that ever existed under Homo sapiens dominance. A kind of civilisation that today is ignored, taken from their environment and still treated as savages.

Moreover, they were thrown into a crumbling contemporary society that dictates itself as advanced, but it cannot even look after the land, rubbish, and people correctly. Instead of listening to the elders that passed on stories after stories about the land, we tend to shut their mouths and do what we think is best. Unfortunately, it is proving to be a failure.

Maybe it is about time to open our eyes and finally realise that we are just like them, human beings willing to survive. And if we could include our ancient people as part of our society, just then our world could be a better place.

Thank you for reading!

Share Post